Agricultural water supplies running thin

Much of the southwest has been in the grips of a record-breaking ‘megadrought’ since 2000. Farmers along the Rio Grande in Colorado and New Mexico have been struggling to make due with less water.

New Mexico receives a portion of Rio Grande’s water each year, as set by the Rio Grande Compact, an interstate water sharing agreement. With reduced water flowing into the state from Colorado, irrigation deliveries to farms in both the middle and the southern parts of the state are diminished by early summer. Elephant Butte Reservoir in southern New Mexico—which could store water to irrigate nearly 200,000 acres—has been nearly dry in recent years. This is due not only to the drought but also to ongoing aridification of the basin.

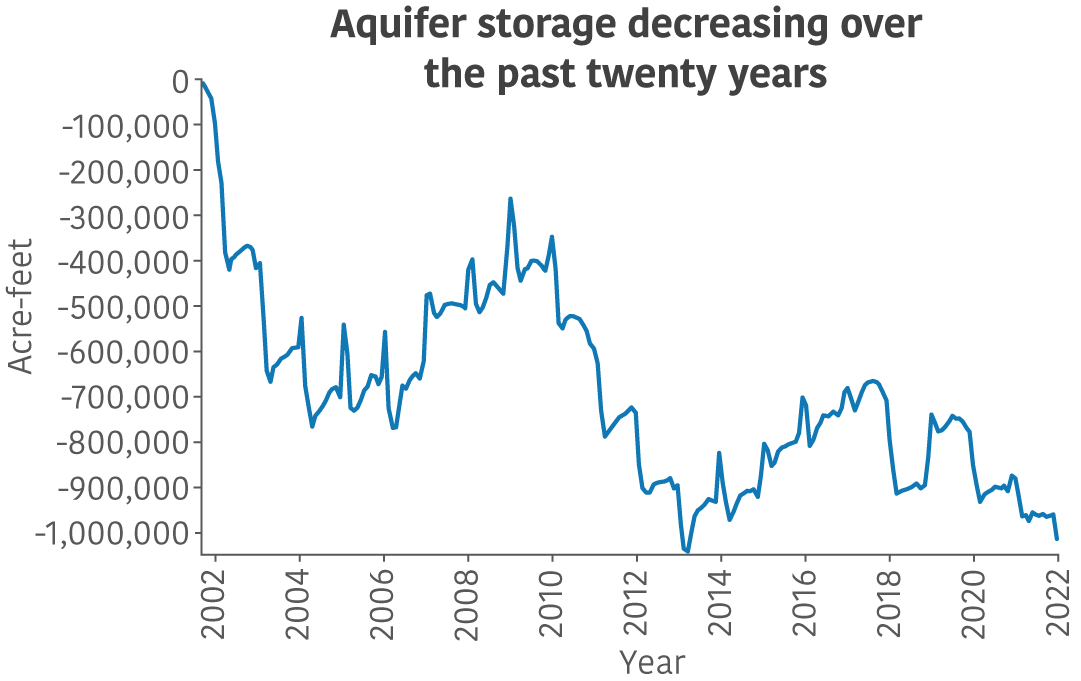

Upstream in the San Luis Valley of Colorado, the water level of a massive aquifer underlying the valley has plummeted as climate change reduces groundwater recharge. Facing the threat of having their wells shut down by the state engineer, farmers formed a water management district and a plan to pay participating farmers to leave their cropland unplanted. Rising aquifer levels during 2013–2018 brought great hope for management success, but the unrelenting and intensifying drought in recent years has erased optimism. However, increasing creative efforts to manage water use can bolster the positive impact of already ongoing actions.

Southwestern willow flycatcher thriving but still needs support

The southwestern willow flycatcher is an endangered subspecies found in the southwest US, including in Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. This bird requires native plant-based habitats and does not thrive where invasive species like saltcedar are dominant. In the Middle Rio Grande, the flycatcher is common during migration in the spring and fall and breeds in willow-dominated riparian areas. The number of flycatcher-preferred territories in the Middle Rio Grande has greatly increased since 2000.

Both the Elephant Butte and Middle Rio Grande management units are meeting the recovery goals for flycatcher territories. This is quite promising and shows that protecting flycatcher preferred habitats is working. The Middle Rio Grande management unit has exceeded its recovery goal of 100 flycatcher territories for the past 18 consecutive years. However, ongoing threats of native habitat decline, reliance on non-native saltcedar, tamarisk beetles, variable nest success, and dynamic reservoir elevations at Elephant Butte indicate this management unit requires continued monitoring and investigation to support the flycatcher and its habitat.

Regional water management reflects a diverse and complex network of governance

There is an overwhelming magnitude of competing uses that the river supports, from agriculture and domestic uses to use by fish, wildlife, and plant communities. However, there is no single authority for management of the Rio Grande—federal, state, and local organizations have authority in different cases.

The cultural importance of water to Rio Grande communities contributes to the resilience of the Rio Grande Basin. Generally, farming is not corporate, there are many acequias with their own local governance and the Pueblos and Tribes use the river for religious ceremonies and farming. In the headwaters the river still flows almost un-impounded except for at Cochiti Dam on the mainstem until the Elephant Butte Reservoir. Irrigation structures are mostly rudimentary with some exceptions. Over time, the government approach to farming changed the nature of the river below Elephant Butte. Concerning the headwaters, that region is under threat due to fires, less snowmelt, and reduction in winter precipitation. Water is the lifeblood of the Upper Rio Grande, the lack of it and the importance for survival are not lost on the people that live here.

Acequias and Native American communities are important water managers, have a deep understanding of the river, and their water rights are senior. Coping with water shortages through reservoir storage may threaten the survival of traditional acequia-focused culture and communities in Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. The Rio Grande Compact between Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas is an agreement on how much water each should receive. Its goals are to remove all causes of present and future controversy among the states and equitably divide the water allocated. The Rio Grande below Cochiti Dam is heavily managed and there is work occurring to manage the system for a variety of needs but metrics are not yet there to guide new management approaches. There are some conflicts between management groups, and not all groups feel that they have a seat at the table. In the end, there is not enough water for all the people and places where it is needed.