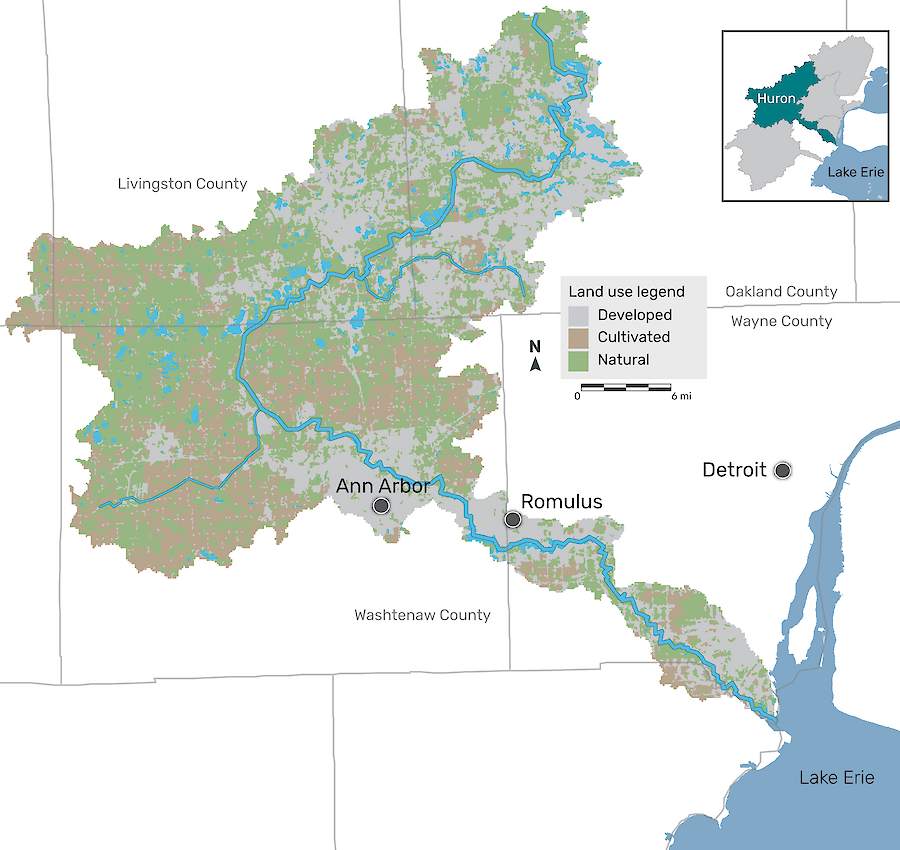

The Huron River (125 mi) meanders through remnant forests, agricultural areas, and a complex series of wetlands, lakes, and urban environments before flowing into the western basin of Lake Erie. Its network of tributaries is made up of 1,200 miles of creeks and streams. The watershed spans a land area of more than 900 square miles that drains to the river. It includes seven Michigan counties and 68 municipal governments, serving 650,000 residents. It contains two-thirds of southeastern Michigan’s public recreation lands and is home to numerous threatened and endangered species and habitat types. The river itself supplies drinking water to over 150,000 people, supports one of Michigan’s finest smallmouth bass fisheries, and is the only designated Scenic River in the area. The Scenic River designation is a testament to careful and effective management of the Huron River and its resources: no small feat in a heavily urbanized region.

The Huron River (125 mi) meanders through remnant forests, agricultural areas, and a complex series of wetlands, lakes, and urban environments before flowing into the western basin of Lake Erie. Its network of tributaries is made up of 1,200 miles of creeks and streams. The watershed spans a land area of more than 900 square miles that drains to the river. It includes seven Michigan counties and 68 municipal governments, serving 650,000 residents. It contains two-thirds of southeastern Michigan’s public recreation lands and is home to numerous threatened and endangered species and habitat types. The river itself supplies drinking water to over 150,000 people, supports one of Michigan’s finest smallmouth bass fisheries, and is the only designated Scenic River in the area. The Scenic River designation is a testament to careful and effective management of the Huron River and its resources: no small feat in a heavily urbanized region.

Michigan’s earliest residents were largely affiliated with the Algonquin nation. This migratory population came to organize themselves into three major tribal cultures—the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potowatomi—forming a loose confederation known as the Three Fires. A fourth group of people, the Wendats (Wyandots), settled in southeastern Michigan. Both the Wendats and the Potowatomi established permanent or semi-permanent villages along the Huron River.

Moving Forward in a Changing World

Water sampling in a tributary.

The most significant threats to the Huron River include stormwater runoff, habitat loss, sediment and nutrient pollution, bacteria, and chemical contaminants. Climate change is a “threat multiplier,” meaning that as patterns in precipitation change and air temperatures increase, the threats to river health are amplified.

Protection of natural lands, especially forests and wetlands in the watershed and the land along creeks and streams, serves to keep the water cool and captures polluted runoff from storms before it reaches the river. In urban areas, similar outcomes are achieved with green stormwater infrastructure like rain gardens that catch and soak in runoff. Removing dams removes the risk of dam failures and restores habitat allowing aquatic biodiversity to recover in ways that make the ecosystem resilient to the shocks of extreme events like floods and drought. Improving and adapting existing infrastructure to higher rainfall will reduce flooding and pollution from runoff. Strategies like these must be deployed rapidly and at-scale. The region’s watershed and river groups are uniquely suited to advancing many of these solutions in partnership with others in the region.

Southeast Michigan is home to nearly half of all Michiganders. The region’s inland lakes and streams are critical to the health and the quality of life of residents. Coordinated and significant federal, state, and local investments in freshwater are needed to improve these natural resources for the benefit of people and wildlife.